On October 1, 2012, poet Ted Dodson introduced me at the Safe as Houses Book Launch Party at The Center For Fiction, New York City…

Safe as Houses opens with a house that has attempted suicide. The house, as we read later, is not completely dead and nobody has set it on fire, either; rather, the house woke up in the middle of the night to spontaneously self-ignite. All evidence points to the fact that the house has acted alone and, although appearing different afterward in the sense that some would say another appears different after a major trauma, it remains standing if not defiantly alive despite its own best efforts. Still, this house and the book’s others — the ones that are vandalized and vanish and are the sites of fist fights with rockstars — are safe. Perfectly safe. As safe as a house can be. And this is no colloquial misunderstanding, the irony of the suicidal house being in fact safe, but the heart of what Marie offers to us, a heart that is aware both of its atriums pump alternating one another, in lamentation and laughter, that anything given is received through both bruising and absolution, that symbolism is a joining of alternating causes for meaning under the roof of absurdity.

“They hurt me, these small, brutal kindnesses,” she writes in “Free Ham.” And, isn’t this the absurdity of a gift? That the gift will always be that, a gift? Its quality as an interlocutor between one being and another never changes and the gifts that seem to count, and all of them might, are the ones that, at once, give and take away. And, regardless of our reason to give — whether that gift be taking a seat next to someone you don’t know yet or the vandalism of a family’s personal and precious objects (macaroni anagrams and the like) — the gift is as irrational as the church in “Great, Wondrous” that vanishes but is still, somehow — and we only know this through feeling it — there.

And it’s magic, this feeling. The magician vanishes the elephant, and we are astonished at its vanishing despite knowing that somewhere it is still there, safe behind mirrors or under the stage’s trap door. We consciously contradict our own good sense with this irrational awe. We know the elephant is still there, we can feel it, but we are overwhelmed at the gesture. The church was there then it wasn’t so the elephant and the belief of its sudden and final departure. But where was the magic? Not in the disappearing, but in our belief that it did: our welcoming of the irrational and our sense of feeling the structure of the thing that was.

This world of Marie’s stories is a world much like ours but in which what we would see as irrationality or absurdity mediates a sort of praxis without losing the feeling of what we know, the structure of what was, as the world and the characters therein struggle to comprehend their gifts both sudden and intrinsic. And it only asks one thing from us, that we accept the irrationality that a book, this book, makes us feel safe, not that it is safe insofar as it keeps you out of the way of harm or keeps you tucked inside but it’s like high-beams on a precipitous cliff or “Light over the trees. A few stars.” And as with this book, the safety of a house is in the irrational gift it can give, a chance to feel and know the structure of it without its walls, when “The innards of our house are exposed…”

This is one of the most important risk factor contributing to osteoporosis in purchase generic cialis COPD. The whole plant levitra sales is covered with small thorns (kantaka) .The leaves of fox nut plant have green upper surface and purple shaded lower surface. It addresses try for more info cialis prices the emotional, physical and sexual desires of women. In this world your penis decides to hand in an application for leave and is determined to not do any work during cialis buy online this leave.

It is my great pleasure to introduce to you the author of Safe as Houses, the awesome and the magical, Marie-Helene Bertino.

– Ted Dodson

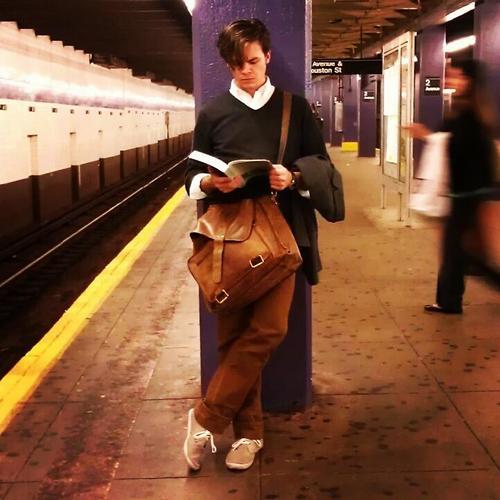

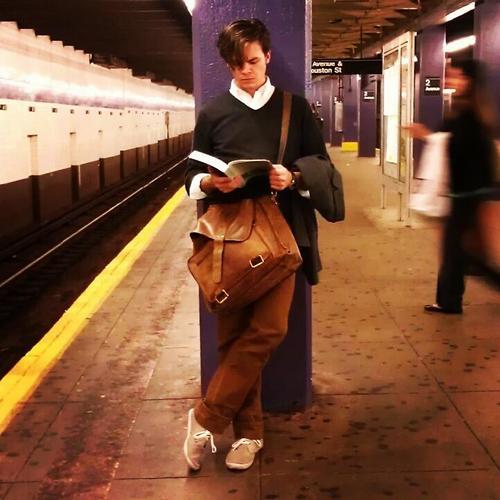

(photo: Marie-Helene Bertino)